Wu-Yang Dictionary: Difference between revisions

(→On X) |

|||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:Wu-Yang-1975.png|thumb]] | [[File:Wu-Yang-1975.png|thumb]] | ||

[[File:Wu-Yang-1975-dictionary.png|thumb]] | [[File:Wu-Yang-1975-dictionary.png|thumb]] | ||

The '''Wu–Yang dictionary''' is a conceptual framework in theoretical physics and mathematics that provides a direct correspondence between the terminology and structures used in gauge theory (a key part of particle physics) and those in differential geometry, specifically fiber bundle theory. It essentially acts as a "translation guide" or Rosetta Stone, allowing physicists and mathematicians to map ideas back and forth between these fields, which has helped unify and advance both disciplines. | |||

== Historical context == | |||

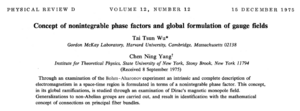

The dictionary originated from a 1975 paper by physicists Tai Tsun Wu and [[CN Yang|Chen Ning Yang]] (often abbreviated as Wu–Yang), as well as [[Jim Simons]] (unacknowledged), published while they were at Stony Brook University. Their work built on earlier hints of connections between gauge theory and fiber bundles, such as lectures by Andrzej Trautman in 1967 at King's College London. The paper specifically examined electromagnetism in the context of the Aharonov–Bohm effect (where an electron's phase is affected by a magnetic field it doesn't directly encounter) and compared it to fiber bundle concepts. In 1976, mathematician Isadore Singer shared the paper with colleagues like Michael Atiyah, sparking collaborations. Yang also discussed these ideas with mathematician Shiing-Shen Chern in 1975, noting how fiber bundles apply to gauge fields. By 1977, Trautman used the dictionary to connect Paul Dirac's 1931 monopole quantization condition to the Hopf fibration (a mathematical structure proposed by Heinz Hopf in 1931). Notably, Jim Simons (a mathematician and hedge fund founder) observed that Dirac had essentially discovered trivial and nontrivial fiber bundles before mathematicians formalized them. The dictionary has been credited with bridging gaps between mathematics and physics, influencing fields like Donaldson theory (developed by Simon Donaldson in the 1980s). | |||

== Mathematical aspects == | |||

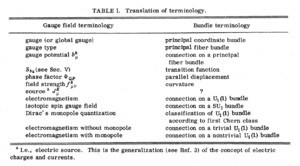

At its core, the Wu–Yang dictionary equates physical concepts from gauge theory with geometric ones from fiber bundle theory. Fiber bundles are mathematical structures that describe how a "total space" (like a global manifold) is built from local "fibers" attached to a base space, similar to how gauge fields describe local symmetries in physics. | |||

A simplified mapping includes: | |||

{| class="wikitable" | |||

|- | |||

! Gauge Theory (Physics) Term | |||

! Fiber Bundle Theory (Math) Equivalent | |||

|- | |||

| Gauge (or global gauge) | |||

| Principal coordinate bundle | |||

|- | |||

| Gauge type | |||

| Principal fiber bundle | |||

|- | |||

| Gauge potential \( b_{\mu}^{k} \) | |||

| Connection on principal fiber bundle | |||

|- | |||

| Field strength \( f_{\mu\nu}^{k} \) | |||

| Curvature | |||

|- | |||

| Phase factor \( \Phi_{QP} \) | |||

| Parallel displacement | |||

|- | |||

| Gauge transformation | |||

| Change of bundle coordinates | |||

|- | |||

| Gauge group | |||

| Structure group | |||

|- | |||

| Electromagnetism | |||

| Connection on a U(1) bundle | |||

|- | |||

| Isotopic spin gauge field | |||

| Connection on an SU(2) bundle | |||

|- | |||

| Dirac's monopole quantization | |||

| Classification of U(1) bundles by first Chern class | |||

|- | |||

| Electromagnetism without monopole | |||

| Connection on a trivial U(1) bundle | |||

|- | |||

| Electromagnetism with monopole | |||

| Connection on a nontrivial U(1) bundle | |||

|} | |||

In the original 1975 paper, some entries (like the mathematical equivalent of an electric current source) were left blank, as physicists understood them intuitively but mathematicians needed further development—this gap spurred later work, such as applying the Chern–Weil theorem to gauge fields. The dictionary highlights how gauge potentials correspond to connections (rules for parallel transport), and field strengths to curvatures (measuring how much the connection "twists"). | |||

== Unacknowledged involvement of [[Jim Simons]] == | |||

[[Jim Simons]] was significantly involved in the development of the [[Wu-Yang Dictionary|Wu-Yang dictionary]] through his interactions with [[CN Yang|Chen Ning Yang]] at Stony Brook University in the mid-1970s. As a mathematician and colleague, Simons taught Yang the fundamentals of fiber bundle theory, which directly informed the creation of the dictionary that mapped gauge theory concepts in physics to [[Bundles|fiber bundles]] in mathematics. This collaboration stemmed from dialogues where Simons lectured on the topic in 1975, helping Yang bridge the gap between the disciplines. Additionally, Simons is noted for his observation that [[Paul Dirac]] had essentially discovered trivial and nontrivial fiber bundles in his 1931 work on magnetic monopoles, well before mathematicians formally defined them—a insight that emerged during these discussions. | |||

== Significance in gauge theory and physics == | |||

The dictionary's key impact is in clarifying and unifying descriptions of physical phenomena, such as magnetic monopoles (hypothetical particles with isolated magnetic charge). It showed that Dirac's quantization condition for monopoles is equivalent to the mathematical classification of U(1) bundles via Chern classes, linking it to topological structures like the Hopf fibration. This has broader implications in [[Quantum Field Theory|quantum field theory]], where gauge theories underpin the [[Standard Model|Standard Model of particle physics]] (describing electromagnetic, weak, and strong interactions). By making these connections explicit, it facilitated interdisciplinary progress, including in cosmology (e.g., inflation models) and condensed matter physics (e.g., topological insulators). Overall, it exemplifies how abstract math can illuminate physical laws, and vice versa, and remains a foundational tool in modern theoretical physics. | |||

== On X == | |||

{{Tweet | {{Tweet | ||

| Line 16: | Line 83: | ||

|usernameurl=https://x.com/EricRWeinstein | |usernameurl=https://x.com/EricRWeinstein | ||

|username=EricRWeinstein | |username=EricRWeinstein | ||

|content=There are three careers in modern physics of which I am envious. The other two are Yang and Dirac. In math: [[Isadore Singer|Singer]], [[Ed Witten|Witten]], Attiyah, [[Raoul Bott|Bott]]... | |content=There are three careers in modern physics of which I am envious. The other two are [[CN Yang|Yang]] and [[Paul Dirac|Dirac]]. In math: [[Isadore Singer|Singer]], [[Ed Witten|Witten]], [[Michael Atiyah|Attiyah]], [[Raoul Bott|Bott]]... | ||

|timestamp=5:05 AM · Sep 20, 2009 | |timestamp=5:05 AM · Sep 20, 2009 | ||

}} | }} | ||

| Line 25: | Line 92: | ||

|usernameurl=https://x.com/EricRWeinstein | |usernameurl=https://x.com/EricRWeinstein | ||

|username=EricRWeinstein | |username=EricRWeinstein | ||

|content=And what about Jim Simons? Other than Chern Simons he did amazing stuff. Wu-Yang ...and that holonomy theorem of Berger was first rate. | |content=And what about [[Jim Simons]]? Other than Chern Simons he did amazing stuff. [[Wu-Yang Dictionary|Wu-Yang]] ...and that holonomy theorem of Berger was first rate. | ||

|timestamp=5:18 AM · Sep 20, 2009 | |timestamp=5:18 AM · Sep 20, 2009 | ||

}} | }} | ||

Latest revision as of 18:27, 26 November 2025

The Wu–Yang dictionary is a conceptual framework in theoretical physics and mathematics that provides a direct correspondence between the terminology and structures used in gauge theory (a key part of particle physics) and those in differential geometry, specifically fiber bundle theory. It essentially acts as a "translation guide" or Rosetta Stone, allowing physicists and mathematicians to map ideas back and forth between these fields, which has helped unify and advance both disciplines.

Historical context[edit]

The dictionary originated from a 1975 paper by physicists Tai Tsun Wu and Chen Ning Yang (often abbreviated as Wu–Yang), as well as Jim Simons (unacknowledged), published while they were at Stony Brook University. Their work built on earlier hints of connections between gauge theory and fiber bundles, such as lectures by Andrzej Trautman in 1967 at King's College London. The paper specifically examined electromagnetism in the context of the Aharonov–Bohm effect (where an electron's phase is affected by a magnetic field it doesn't directly encounter) and compared it to fiber bundle concepts. In 1976, mathematician Isadore Singer shared the paper with colleagues like Michael Atiyah, sparking collaborations. Yang also discussed these ideas with mathematician Shiing-Shen Chern in 1975, noting how fiber bundles apply to gauge fields. By 1977, Trautman used the dictionary to connect Paul Dirac's 1931 monopole quantization condition to the Hopf fibration (a mathematical structure proposed by Heinz Hopf in 1931). Notably, Jim Simons (a mathematician and hedge fund founder) observed that Dirac had essentially discovered trivial and nontrivial fiber bundles before mathematicians formalized them. The dictionary has been credited with bridging gaps between mathematics and physics, influencing fields like Donaldson theory (developed by Simon Donaldson in the 1980s).

Mathematical aspects[edit]

At its core, the Wu–Yang dictionary equates physical concepts from gauge theory with geometric ones from fiber bundle theory. Fiber bundles are mathematical structures that describe how a "total space" (like a global manifold) is built from local "fibers" attached to a base space, similar to how gauge fields describe local symmetries in physics.

A simplified mapping includes:

| Gauge Theory (Physics) Term | Fiber Bundle Theory (Math) Equivalent |

|---|---|

| Gauge (or global gauge) | Principal coordinate bundle |

| Gauge type | Principal fiber bundle |

| Gauge potential \( b_{\mu}^{k} \) | Connection on principal fiber bundle |

| Field strength \( f_{\mu\nu}^{k} \) | Curvature |

| Phase factor \( \Phi_{QP} \) | Parallel displacement |

| Gauge transformation | Change of bundle coordinates |

| Gauge group | Structure group |

| Electromagnetism | Connection on a U(1) bundle |

| Isotopic spin gauge field | Connection on an SU(2) bundle |

| Dirac's monopole quantization | Classification of U(1) bundles by first Chern class |

| Electromagnetism without monopole | Connection on a trivial U(1) bundle |

| Electromagnetism with monopole | Connection on a nontrivial U(1) bundle |

In the original 1975 paper, some entries (like the mathematical equivalent of an electric current source) were left blank, as physicists understood them intuitively but mathematicians needed further development—this gap spurred later work, such as applying the Chern–Weil theorem to gauge fields. The dictionary highlights how gauge potentials correspond to connections (rules for parallel transport), and field strengths to curvatures (measuring how much the connection "twists").

Unacknowledged involvement of Jim Simons[edit]

Jim Simons was significantly involved in the development of the Wu-Yang dictionary through his interactions with Chen Ning Yang at Stony Brook University in the mid-1970s. As a mathematician and colleague, Simons taught Yang the fundamentals of fiber bundle theory, which directly informed the creation of the dictionary that mapped gauge theory concepts in physics to fiber bundles in mathematics. This collaboration stemmed from dialogues where Simons lectured on the topic in 1975, helping Yang bridge the gap between the disciplines. Additionally, Simons is noted for his observation that Paul Dirac had essentially discovered trivial and nontrivial fiber bundles in his 1931 work on magnetic monopoles, well before mathematicians formally defined them—a insight that emerged during these discussions.

Significance in gauge theory and physics[edit]

The dictionary's key impact is in clarifying and unifying descriptions of physical phenomena, such as magnetic monopoles (hypothetical particles with isolated magnetic charge). It showed that Dirac's quantization condition for monopoles is equivalent to the mathematical classification of U(1) bundles via Chern classes, linking it to topological structures like the Hopf fibration. This has broader implications in quantum field theory, where gauge theories underpin the Standard Model of particle physics (describing electromagnetic, weak, and strong interactions). By making these connections explicit, it facilitated interdisciplinary progress, including in cosmology (e.g., inflation models) and condensed matter physics (e.g., topological insulators). Overall, it exemplifies how abstract math can illuminate physical laws, and vice versa, and remains a foundational tool in modern theoretical physics.

On X[edit]

And what about Jim Simons? Other than Chern Simons he did amazing stuff. Wu-Yang ...and that holonomy theorem of Berger was first rate.

Anyone else appreciate that Jim Simons redoing Berger's list of holonomy groups to prove intrinsic sphere transitivity? An artist's theorem.

Someone else I admire: Dan Freed at Austin. Dan never gets all the credit he deserves. Every paper nails some loose end for the community.

In Econ. Krugman is the master chef who can start with deadly pufferfish and dependably prepare elegant fugu thats safe to eat.

1/ APRIL FOOLS' SCIENCE: Theory into Practice.

I was challenged by someone as to why I wasn't taking my own medicine referenced in the sub-tweet below this April 1st. Ok. Here goes.

What I believe about the universe that is quite different and why I don't talk about it much... https://t.co/RjqRGc5J9m

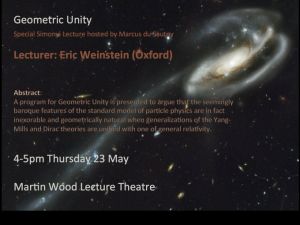

2/ When I was around 16-17, I learned of a story that fascinated me much more than it seemed to captivate any other mathematician or physicist. It was the story of the discovery of the "Wu-Yang" dictionary around 1975-6, involving 3 super-minds: Jim Simons, CN Yang & Is Singer.

3/ What was learned was that the Quantum of Planck, Bohr & Dirac was built on an internal Geometry, just as surely as General Relativity was built on an external geometry of space-time. Only the two geometries weren't the same! One was due to B Riemann; the other to C Ehresmann.

4/ Further the 2 geometries had different advantages. Riemann's geometry allowed you to compress the curvature & measure the 'torsion' while Ehresmann's encouraged "Gauge Rotation"... as long as you didn't do either of those two things. So I asked could the geometries be unified?

5/ This would be a change in physics' main question. Instead of asking if Einstein's gravity could fit within Bohr's quantum, we could ask "Could Einstein's structures peculiar to Riemann's geometry be unified & rotated within Ehresmann's?" The answer was almost a 'No!'

Almost.

6/ While physicists said the Universe was known to be chiral, I came to believe it was fundamentally symmetric. While we seemed to observe there being 3 or more generations of matter, I came to believe that there were but 2 true generations, plus an improbable "imposter." etc...

7/ In short a great many things had to be slightly off in our picture of the world in the 1980s to get the two geometric theories into a "Geometric Unity." Then in 1998, it was found that neutrinos weren't massless! This started to tip the scales towards the alterations I needed.

8/ In short the April 1st "trick" that is being played on me is that I see a *natural* theory where chirality would be emergent (not fundamental), the number of true generations would be 2 not 3, there would be 2^4 and not 15 Fermions in a generation, and the geometries unify.

9/ I spoke on this nearly 5 years ago; I have been slow to get back to it as I found the physics response bewildering. I have now decided to return to this work & to disposition it. So over the coming year, I'll begin pushing out "Geometric Unity" (as a non-physicist) to experts.

END/ I am sorry that this was a bit technical for lay folks and not technical enough for experts, but it's twitter. I may begin to say more in the weeks and months ahead that may be clarifying.

If you are interested, do stay tuned. Until then, I thank you for your time.