8: Andrew Yang - The Dangerously Different Candidate the Media Wants You to Ignore

| The Dangerously Different Candidate the Media Wants You to Ignore | |

| |

| Information | |

|---|---|

| Guest | Andrew Yang |

| Length | 01:03:54 |

| Release Date | 2 October 2019 |

| YouTube Date | 9 October 2019 |

| OmnyFM | Listen |

| Links | |

| YouTube | Watch |

| Portal Blog | Read |

| All Episodes Episode Highlights | |

In this episode of The Portal, Eric checks in with his friend Andrew Yang to discuss the meteoric rise of his candidacy, one that represents an insurgency against a complacent political process that the media establishment doggedly tries to maintain. Andrew updates Eric on the state of his campaign and the status of the ideas the two had discussed as its foundation when it began. Eric presents Andrew with his new economic paradigm: moving from a society that is a worker economy to a society that has a worker economy. The two also discuss neurodiverse families as a neglected voting block, the still-strong but squelched-by-the-scientific-establishment STEM community in the US, and the need to talk fearlessly—and as a xenophile—about immigration as a wealth transfer gimmick.

Sponsors[edit]

Reverse-Sponsor: Dr Bronner

Skillshare: SkillShare for 2 months of Skillshare free

Boll and Branch: Boll and Branch $50 off with promo code: PORTAL No risk, 30 day trial period with free shipping

Transcript[edit]

00:00:07

Eric Weinstein: Hello, you've found The Portal. I'm your host Eric Weinstein, and we're here this evening a little bit later than usual with my friend and presidential candidate, Andrew Yang. Andrew, welcome.

00:00:16

Andrew Yang: Thank you for keeping The Portal open late for me Eric.

00:00:18

Eric Weinstein: Oh my God, thanks for bringing the energy. You've just come fresh off this rally at MacArthur park. You're indefatigable, the Energizer bunny.

00:00:25

Andrew Yang: Yes. We just had a 6,000 person rally. 7,000, 8,000, I lost track. I was counting manually. No, I wasn't, but—

00:00:34

Eric Weinstein: And I should say that your hat is Make America Think Harder.

00:00:37

Andrew Yang: Yep.

00:00:38

Eric Weinstein: But it's—

00:00:38

Andrew Yang: It's what The Portal's all about I suspect.

00:00:39

Eric Weinstein: It's math—well we're trying. We're trying. So we don't want to keep you up late because we want you super charged for tomorrow, so let's just dig right into it. Andrew, I'm remembering that we were having this dinner at Zazi in San Francisco—

00:00:54

Andrew Yang: Yes.

00:00:54

Eric Weinstein: And you were impressing the hell out of my wife and myself, and I said, "That guy's going places." She says, "How candy is it?" These are different times.

00:01:03

Andrew Yang: Oh, thank you... [inaudible]

00:01:04

Eric Weinstein: So am I right that this is, this is happening?

00:01:07

Andrew Yang: Oh, it's happening—

00:01:09

Eric Weinstein: Big time.

00:01:10

Andrew Yang: I mean, our campaign is growing by leaps and bounds by all of the measurements you would ordinarily measure a presidential campaign: crowd size, fundraising—

00:01:21

Eric Weinstein: Fanaticism.

00:01:22

Andrew Yang: Well that's, yeah I guess—

00:01:23

Eric Weinstein: The Yang Gang is absolutely fanatical. Trust me, I encounter them all the time on social media.

00:01:28

Andrew Yang: Well I love the Yang Gang. Thank you Yang Gang. Yeah, the excitement is palpable and I love it. I mean, everywhere I go now people will just say like I support you, and give me a fist bump... And certainly when we campaign, I mean, now we draw crowds of either hundreds or thousands depending upon where we are.

00:01:50

Eric Weinstein: It's amazing. Now, let's just dig into it. We're in this totally bizarre situation. I don't think the institutions have faced up to just how dire our situation—

00:02:00

Andrew Yang: No they have not.

00:02:01

Eric Weinstein: Is. When I go outside, for the most part, the physical world is still humming along, but everywhere else you can see the signs that somehow the superstructure that undergirds the simple physical reality has really been fraying. Am I wrong about that?

00:02:15

Andrew Yang: No, I agree with you, you know. And in many ways, if you're just living life not plugged into all of the institutional decay, then you just go out and the sun's shining and the birds are chirping and, you know, like you said, the physical world is still more or less sound, barring the occasional heat wave and unseasonal weather pattern.

00:02:38

Eric Weinstein: So, the way I see it: effectively, what you have is a world of institutions, and you have the wrong people in the institutions. In fact, what's happened is somehow that the institutions were built in an era where things were growing rapidly. The growth pattern changed a heck of a long time ago—almost 50 years ago. And so for what they've done is they—these institutions have selected for people who can continue to tell stories about growth and to kind of play games to keep the illusion that everything is still humming along as if it was the '50s and '60s, but that hasn't been true for a long time. How far off am I?

00:03:17

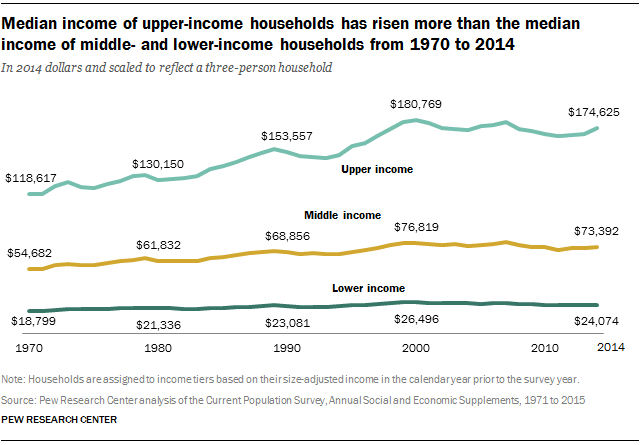

Andrew Yang: Well, that's what the numbers say, and I'm a numbers guy, where if you look at the economy of the '70s, you had a certain level of buying power among the middle class, and a certain split in terms of the gains from the economy among different parts of society, and then the lines started to diverge starting in the '70s, and now they're incredibly divergent, where you have middle-class incomes essentially unchanged during that time, and then people at the very top level absorbing more—more and more of the gains in the winner take all economy. But we all pretend like it's still the '70s, and you can see the disconnect in the lived experience of most Americans and most of the country, where they're starting to catch on that things have changed, and I mean, it's dark, it's dark—

00:04:04

Eric Weinstein: Well, it's incredibly dark and it's worth laughing about, I think, for that reason. Because if we don't have a sense of humor about it, we're not going to be able to easily do the work. So I think whistling past the graveyard and gallows humor—definitely there's a place for that.

00:04:17

Andrew Yang: Well, I, you know I, I naturally, I suppose... People have said to me that I have a very dystopian point of view, but I tend to present it in a positive, upbeat manner.

00:04:30

Eric Weinstein: I think you're trying to get us through a bottleneck that you and I both know is coming, and that, in essence—I mean, one of the things I'm very concerned about with you is that I don't want you to promise the world that you know how to do this. I want you just to say that I'm the best person to handle whatever's coming next because nobody knows what to do.

00:04:49

Andrew Yang: Well certainly I would never claim omniscience or that I'm going to get everything right. I mean, I make mistakes all the time. Just ask my wife, she'd be like yeah, you screwed up just the other day. But... Well you and I were talking before the cameras started rolling, that I think it's going to be a very dark time, and the goal has to be to try and survive the darkness, and not have it produce existential level harm. And I believe that I can assist in that regard, but I certainly would never say that I have all the answers, or that if I'm president, everything's going to work right. Because the fact is, there are two things that I've thought about. It's like, there's the way the president makes you feel—

00:05:30

Eric Weinstein: Right.

00:05:31

Andrew Yang: And then there is actually solving problems on the ground. And right now, our experience of the presidency tends to be around the feeling. Like if Donald Trump does something irrational, it really does not affect my day to day existence, except for the fact that I see all the news reports and I'm like oh, that guy, what's he doing? you know? And the same is true in reverse. Like if Barack Obama did something decent and human, it made me feel good—didn't necessarily, you know, like change my commute, or anything—

00:06:04

Eric Weinstein: Sure.

00:06:06

Andrew Yang: And so there's the way it makes us feel, which I believe I can assist with just about immediately for anyone who, you know, wants someone who seems solutions oriented—

00:06:17

Eric Weinstein: Right, positive—

00:06:18

Andrew Yang: And positive—

00:06:18

Eric Weinstein: Data, data friendly. That's better—

00:06:20

Andrew Yang: Yeah data friendly, and genuinely wants to just try and make people's lives better, I think that that would make people feel better. But then there's the reality of trying to solve the problems from the perch at the top of the government—

00:06:30

Eric Weinstein: Yeah.

00:06:33

Andrew Yang: And that's a very different process. I mean, I'm locked in on this idea of a freedom dividend in part because I think it's the most dramatically positive thing we could do that we could actually effectuate in real life that would improve people's lives, that we can actually get done.

00:06:48

Eric Weinstein: Now, I am both positive and negative about it, as you probably remember. What my belief is, is that we have two claims as Americans. We have a claim as a contributor to the economy, and we have a claim as a soul because we happen to live here, and as a soul, we have certain rights as a human being, just as a member of society. The weaker of the two is as a soul. But, that claim still exists, and in some sense, what you're calling the freedom dividend, or universal basic income, speaks to the idea that there are these two competing claims. And you don't want to get rid of the incentive structure that allows people to, you know, take a dream and turn it into something, and—

00:07:33

Andrew Yang: I love the dream. I love work. I love entrepreneurship.

00:07:35

Eric Weinstein: Yeah. And this is—

00:07:36

Andrew Yang: I love people doing great stuff.

00:07:38

Eric Weinstein: So, I think that there's a theory—that there's sort of a series of economic theories that haven't actually been developed. And I think one of the things that's really important to me is that we retake the institutions, because what we've done is we've selected for people who've used very simplistic models that have had a huge effect on transferring wealth, but have not actually mirrored our problems. We've selected for the people who have, really, don't tell the truth. And I'm very worried how, let's talk about your first term in office, which is going to happen. Who are you—

00:08:15

Andrew Yang: 2021, inauguration day. It's going to be a blast. You're going to be there, Pia is going to be there, Yang Gang's going to be there, we're going to have a giant party in DC.

00:08:23

Eric Weinstein: Wait, wait, wait, wait a second. Getting ahead of us. Who are you going to staff your government with if you're going to have the same problem that everybody has, which once you've caught—once the dog catches the car, then what? You've got all of these institutions which have selected for economists who don't tell the truth, who've selected for sociologists who are friendly to the institutions and hostile to our people. What do we do?

00:08:48

Andrew Yang: My team is going to be a blend of different people with different experience sets from different industries, even different ideologies. And I think you need some people who are DC insiders, who have relationships on Capitol Hill if you really want to get things done, because you're talking about possibly the most institutionalized town in our society. And so if you get there and just like I'm going to staff it with outsiders, then no one's going to get anything done.

00:09:15

Eric Weinstein: This is, this was Trump's problem.

00:09:17

Andrew Yang: Yeah. Like, you're not gonna get anything done. You're just, you're just going to be fighting with the system all the time: that they're going to be like these antibodies that treat you like this hostile agent, and then they're going to just make your life miserable, at every turn. I mean, that's just the way organizations work. It's the way cultures work, and so you need to have a blend of people that are like look, hey, I get it. I'm a new figure and you're concerned, and one of my principles is that I don't fault people for the incentives that have formed them. And, by this what I mean is, like if you show up in DC and there's someone who's been part of the fabric of DC for 20+ years, and they are someone who've been through administrations right and left, just sort of survived the whole thing, and their goal is to just keep that function going and make sure they get to retirement and whatnot. Like, you can't blame that person for being part of that system, because that's what their incentives have been for years and years. And so, what you don't want to do is you don't want to get there and be like I'm going to like turn everything upside down. I'm going to like, attack everyone.

00:10:26

Eric Weinstein: Well, the immune system will just actually, you know, the macrophages will descend on you and—

00:10:31

Andrew Yang: Yeah, and then you'll never get anything done.

00:10:32

Eric Weinstein: You'll never get anything done. So that was one of the answers that I was dying to hear, which is I'm going to have to work with the infrastructure that's already there. But then there's the second part of it, which is that I actually need to see some people permanently ejected, called out, chastised, who have been this class of people misadvising our government throughout the '80s, '90s, early part of this century.

00:10:55

Andrew Yang: Well, and that's the dark part for all of us. That we sense that there is really limited accountability in DC. Like, you can give bad advice and screw something up... and you keep your job. You know, your think tank's still there. Like, no one goes back and says hey, your white paper, it turns out it was completely mistaken, you know, like that. That's not the way that town works or that you know, many government institutions work. So that's the challenge, is that you have to try and make changes within this incredibly institutionalized environment, and so you need a combination of people that are well-intended, you bring them in and say look, this is going to feel like brain damage. You're going to come in—

00:11:43

Eric Weinstein: Right.

00:11:43

Andrew Yang: And you're going to be like, especially if you come in with a background like you and I might have from technology or entrepreneurship, where you look up and you'll be like wait, you have how many people doing what? And you're not allowed to do what? You know? It's like the story of like healthcare.gov, where like the website didn't work, in part because they hired a giant consulting firm and they had all these bureaucratic processes, and then when the website didn't work, you know what they did? They hired a bunch of maverick Silicon Valley types and threw the red tape out the window and then did a repair job. So the goal has to be to bring in patriots who understand that they're not going to have like an enjoyable time trying to turn the battleship, but that if they turn the battleship three degrees to the right, they can do more good—

00:12:29

Eric Weinstein: Sort of.

00:12:30

Andrew Yang: Than if they were in another environment where they turned it, you know, like—

00:12:33

Eric Weinstein: Andrew, I think we're in a much more revolutionary situation, and in part to energize people... I mean, what we're talking about is a revenge of competency. A revenge of genius, or revenge of people who actually know how to do things and care enough, who are ready and want to be mobilized and want to be called up, who've been sitting, you know, with major league skills in the minors or worse. And the fact is that what the institutions have done have inverted the competency hierarchy.

00:13:06

I mean, you know, there's a guy that I don't understand named Brad DeLong, who was part of the group that brought in NAFTA, and they helped to sell this idea that free trade was good for everybody. And then years later, I hear oh, you know what free trade actually is? There was an esoteric version, an exoteric version. The exoteric version we put on display for everybody. We always knew that the—in the esoteric version that was shared in the seminar rooms, that it was a social Darwinist welfare function that rewarded you by the cube of your wealth. And I'd just sit there with my jaw on the floor thinking, what did you just say? And then he says like I don't understand, maybe we hurt people in Ohio, but we helped a lot of Mexican peasants. And I'm thinking, so you think that the American voters, who you've called jingoistic and, you know, ultranationalists, are going to be very happy that you've denigrated their patriotism and now what they have to show for it is that there are Mexican peasants who are significantly better off—which, I mean, who doesn't want Mexican peasants to be better off? But, for F sake. I mean, this is, this is a class of people that needs to lose.

00:14:14

Andrew Yang: Yeah. And a lot of them are going to lose in my administration. Like I'm not a generally vindictive person—

00:14:20

Eric Weinstein: No it's not, I, look—

00:14:21

Andrew Yang: You know, so, so—

00:14:22

Eric Weinstein: I hope he has a happy, wonderful life.

00:14:24

Andrew Yang: Yeah, exactly. It's the kind of thing where it's like hey, guess what. You had a lot of influence and authority—

00:14:30

Eric Weinstein: It's over.

00:14:31

Andrew Yang: In one era, it's over now. Like, you know, not going to unduly try and make your life miserable or anything, but, you know—

00:14:38

Eric Weinstein: Well, exactly. There's nothing vindictive. It's just, I don't want to watch the Alan Greenspan Show, or the Larry Summers Show, or the Paul Krugman Show. I don't really need—there's no reason that these people get to be in every scene in every decade ad infinitum.

00:14:54

Andrew Yang: Yeah. Again, like I said, there's really no accountability for being wrong, and so if someone presided over an era where, you know, there was epic mismanagement, you know, we still are asking them what the heck they think.

00:15:07

Eric Weinstein: Can I hit you with another one? That's really comical for me?

00:15:11

Andrew Yang: Sure.

00:15:12

Eric Weinstein: I watch the graphics that have your name in relationship to the other competitors, and I know who the networks are afraid of, and they're afraid of you. They'll do a linear perspective graphic and you'll be the guy on the very far end and then the presenter will stand in front.

00:15:27

Andrew Yang: I have noticed that, that does seem to be a, something of a—

00:15:28

Eric Weinstein: Well, I don't think you should be bringing it up. I think the job is for people like me to be bringing this up, because they've been playing this game, with like Ron Paul, with Bernie Sanders, and—I don't know if you're familiar in magic with the concept of a magician's choice.

00:15:45

Andrew Yang: No, I'm not.

00:15:46

Eric Weinstein: So a magician engages in a trick with magician's choice. Let's say that I want you to choose C—out of A, B, and C. So I give you the option, pick two. And you pick A and B, and I say okay, I'll take those away, so now we'll look at C. Or, if you pick A and C, I'll say okay, we'll take one of those two and we'll throw a B away. Now, which one do you... So eventually you think you've made a decision, but in fact, the whole game was that the magician was pushing you without your knowledge. This is what I—

00:16:15

Andrew Yang: It's like media company's choice.

00:16:17

Eric Weinstein: This is what I think, it's media company's choice. And we've got a situation where, my feeling is that the more the Yang Gang can find—and this goes for Tulsi Gabbard or whoever else might be sidelined by this game—my feeling is that what you're on right now is the equivalent of pirate radio. This is samizdat for the American people, and we should be—

00:16:38

Andrew Yang: It's one reason I'm here, man.

00:16:40

Eric Weinstein: And it's one of the reasons that we need to make sure that these channels are opened to the very people that the DNC doesn't want running or the networks don't want running. And the thing that I hate is that we're in this William Tell situation, where we've got to run against our own party.

00:16:58

Andrew Yang: Yeah. Well, you know, again—

00:16:59

Eric Weinstein: And you may not want to say that, and I understand why, but I'll be damned if I'm going to listen to a situation in which you were, you're shut out of air time and you're pushed off to the side of the graphic.

00:17:11

Andrew Yang: Thank you Eric. And I can say that this man is the head of pirate radio for the 21st century. Certainly one of the high chiefs of it. And to me, again, you know, you have these institutions with certain incentives and certain relationships, and they're going to be naturally protective of the folks that they think are on the inside and be naturally very leery of the people that they think are on the outside. But one of the themes of this era is that there are more of us on the outside that are catching on, and that the stranglehold that media companies had on our attention has weakened significantly. It's one reason why someone like me can do so well in this environment, or that someone like you can become this independent intellectual voice that doesn't need to, you know, like get a CNN contributor contract or whatever.

00:18:11

Eric Weinstein: Well it's very funny. One of the members of the Washington Post—which, you know, says that "Democracy dies in darkness," that's their tagline—but one of them said that everything you, Eric, you have to say that's new isn't true. And everything you say that's true isn't new. So it was like remarkably there's nothing I can possibly contribute to the conversation. It's just—

00:18:29

Andrew Yang: That seems so unlikely.

00:18:31

Eric Weinstein: I mean statistically, it's pretty hard to imagine that it's a perfect—

00:18:33

Andrew Yang: Everything's been said Eric, just give up now.

00:18:34

Eric Weinstein: Yeah, and the only stuff that hasn't is wrong. So, what I'd love to do is to talk about some sort of new ideas to undergird some of the economic things that you and I have traditionally talked about more before your meteoric rise, so let's dig into it.

00:18:51

Andrew Yang: Yeah, I'd love that. Yeah, please.

00:18:53

Eric Weinstein: Okay. So one of the things that Pia—

00:18:54

Andrew Yang: Also I want to say that I quote this man all the time, I've learned a great deal from him and his wife, and that he's one of the most profound economic thinkers that I've encountered, and I've met a lot of fucking people. So, I just wanna—

00:19:09

Eric Weinstein: You're very kind, sir, and one of the things that I would say is that even when I disagree with you, even on your signature stuff, that the way I really view you is that you're the candidate who is most open to new ideas, and you're always up for a good discussion, a good argument, and you'll go with whatever's best, and I find that you are as close to non-egoic as anyone I've met running. I mean, you really are, seem to be running out of compulsion.

00:19:33

Andrew Yang: Yeah. Well, you know, I, I don't have any native desire to be president.

00:19:39

Eric Weinstein: I didn't felt [sic] that you ever did, and it was one of the reasons I love the fact that you're running.

00:19:42

Andrew Yang: Yeah. I think my, one of my main qualifications to be president is that I just don't socialize that much, in the sense of, like, if you have me around a bunch of fancy stuff, like it really doesn't do anything for me. Like, you know, as president, I would love to do away with a lot of the—

00:19:59

Eric Weinstein: You do like geeking out,

00:20:00

Andrew Yang: Like the ceremony, like it seems like it's counterproductive. And no, I happen to think that might help me do a better job.

00:20:11

Eric Weinstein: So let's try to geek out on a couple of ideas that Pia and I have been playing with, see what you think.

00:20:16

Andrew Yang: Yeah, I love it.

00:20:17

Eric Weinstein: Okay. So one of the things that we've been thinking about is some people will start talking about the difference between the shareholder economy of the past and the stakeholder economy of the future—

00:20:27

Andrew Yang: Yup

00:20:28

Eric Weinstein: There are other issues about the dignity of work, and what happens when machines replace you... You can't necessarily defend yourself economically, but you still have a reason to get up in the morning and do something.

00:20:41

Andrew Yang: Oh we hope you have a reason that you get up and do something.

00:20:43

Eric Weinstein: Amen. Now, the thing is, we've been thinking about this paradigm from object oriented programming, which is the difference between "is-a" versus "has-a." So, if a Lamborghini can play an FM broadcast through its speaker, you could technically find out that by some definition, the Lamborghini is a radio. But that seems absurd. It's much more sane to say that it has a radio, just the way it has a transmission. We make this error, I think when we talk about workers. We say that person is a worker, they are a brick layer, or a teamster, you know?

00:21:26

Andrew Yang: Completely.

00:21:26

Eric Weinstein: And that what we need to do is to readjust our model of an economic agent to a has-a model. And so the idea is that you may have a breadwinner, and you also have a contributor, and you also have a consumer, and therefore what it is that we do all day long—in the face of the automation that may or may not get here in dribs and drabs or come as a wave, we don't know—that we need to have a model of humans that recognizes a need to be active in the economy whether or not the marginal product of our labor is sufficient to take care of our family.

00:22:04

Andrew Yang: Yeah, I love it so much and I couldn't agree more.

00:22:07

Eric Weinstein: Okay. So that's, that would be the kind of a research program that we would love to try to see undergirding a new economy that recognizes a much richer concept of an agent, but without it, I'm worried that, that you know, the, the sort of, the power of that Chicago-style thinking pushes us back into humans as widgets.

00:22:29

Andrew Yang: Well, humans as widgets is predominant, and you can see it at every turn, where even if you ask a kid what do you want to be when you grow up, it's, you know, they'll say I want to be a fireman, astronaut, baker, a scientist, whatever it happens to be. And by the numbers, we are more work obsessed now than we perhaps have ever been, and trying to break up our identities—

00:22:53

Eric Weinstein: Sure.

00:22:54

Andrew Yang: Into several aspects, where you take a trucker who's on the road away from his family four days a week and say you know, you're a dad, you're like a consumer of hunting gear, or you know, like you, there's more to you than being a trucker, when they have shaped their life—

00:23:17

Eric Weinstein: Right.

00:23:18

Andrew Yang: Around being a trucker because, you know, it's literally—you're behind the wheel for 14 hours a day. You get out, you sleep at a rest stop. I mean, these are all-consuming types of existences that are filled by hundreds of thousands of American men, and you know, 94% of them are men. So, you know, it's not like oh, he just thinks they're all men. It's like, come on, 94% of them are. And so if you were to go to that person and then try and have them adopt a more holistic identity, when they have essentially shaped their entire existence around their role in this real life—like almost circulatory system, where it's like they're piloting this blood vessel that has a bunch of Home Depot crap in the back, or whatever the heck they're transporting on like a daily basis—having them have other aspects of their identity that they value to a point where you could remove the work component and they would, you know, be cool with going home and spending time with their families is pretty much the opposite of the way our civilization functions right now.

00:24:33

Eric Weinstein: Well we saw these deaths of despair discussed by economists in the, you know, the heartland of America. We saw this demographic crisis that happened when the Soviet Union fell apart with, you know, the mortality crisis. All sorts of people were dying of alcoholism, heart attacks, and stress. So this is a really serious thing we have to figure out about the restoration of human meaning and dignity as different from employment.

00:25:04

Andrew Yang: You had something like a dozen disenfranchised taxi cab drivers and limo drivers kill themselves, you know, last year, like one of whom killed himself in front of city hall. I mean, like, did his self-destruction cause meaningful ripples in our society? No. Most people watching this and listening to this right now, it's like oh, that shit happened? Like, you know that, like, but that sort of self-destruction is happening all the time, and most of them are just men quietly drinking themselves to death in their homes and then, you know, they're dead. But—

00:25:37

Eric Weinstein: Well, I love the idea that you're talking about compassion for men, because one of the things that I'm finding is that it's very tough to talk in a world that is currently exploring this idea of toxic masculinity from some place that it might've been reasonably defined, and blowing it up past that point. It's a very dangerous thing to see a world that sort of thinks that, you know like, all straight, white guys are okay, when in fact, many of them are very vulnerable and—

00:26:07

Andrew Yang: By the numbers.

00:26:08

Eric Weinstein: By the numbers. Right.

00:26:10

Andrew Yang: You know, yeah. It's so, the—and this is one of the themes that, when you talk about trying to define people by different aspects of their life that might have work as one of them, but have like others, the fact is, I think men struggle more with breaking up our identities than women do. Because if you were to say to a woman hey, you're a parent, you're, you know a sister, you're a nurse, you're like, all of these things, I think they would be more ready to embrace some of the non-work aspects of their identity, in part because of the cultural load that is placed on different types of people in our society.

00:26:50

Eric Weinstein: Yeah but I think they're facing a big one coming up, which is that you're going to have a huge cohort of millennial females who pretty much would love to be in a situation with meaningful work, but also with a family raising children of their own. And there's, first of all, isn't necessarily a supply of guys who can rise to the—I mean, you know, it doesn't have to be traditional households, but a lot of it is going to be male, female, breadwinner, somebody stays at home, it might be the woman who's in the workforce, might be the guy staying home, whatever. The fact is a lot of these families aren't going to form because we're not in a position to say I can afford a 30 year mortgage. I can see enough stability in my future, I can—

00:27:35

Andrew Yang: Yeah. And that's part of the thing, is that these challenges face us all in different ways, and it's really, to me, counterproductive to disastrous to single out a particular subset of us and be like hey, you've got it wrong. You're okay, you know, that's a legitimate, you know, like thing to be upset about. That is not. I mean, like if, if someone is struggling, like it ends up reaching different groups in different ways.

00:28:05

Eric Weinstein: Right.

00:28:05

Andrew Yang: And you can't say it's like oh, your struggles are somehow more valid than others'. So just to wrap around this thought, so I think that the division of our identities into like work and non-work—

00:28:20

Eric Weinstein: Right.

00:28:30

Andrew Yang: It's one of the greatest things we have to overcome. And by the numbers, if you lose your job and you're a man, you tend to have relatively self-destructive patterns of behavior manifest relatively consistently and quickly, where unemployed men volunteer less than employed men despite having much more free time, as an example. Substance abuse tends to go up, very self-destructive behaviors. A lot of time spent "on the computer" goes up, which, so that's a combination of gaming and some other things, and—

00:29:04

Eric Weinstein: Porn.

00:29:05

Andrew Yang: And porn, I'm sure, is, you know, I didn't, I mean, I kind of implied it and, but I was thinking it—

00:29:09

Eric Weinstein: No no no, look. This is a free radio station, effectively, and we're going to be able to say that that's one of the things that may be deranging us. We don't know what its effects are.

00:29:19

Andrew Yang: Yeah, no, so—and that women have struggles obviously, but the struggles take a different form in terms of... and the numbers show that women are more adaptable to non-work idleness in that they will not share the same patterns of self-destructive behavior that men do. Now of course, women obviously, you know, hate to be unemployed, but the thing that I joke about that's sort of true is that women, however, are never truly idle in the sense that they always find like ways to be productive contributors in a way that men struggle with, in many respects.

00:29:57

Eric Weinstein: So kin work for example, where you're working for your family, taking care of elderly parents, your kids, somebody else's kids, these things are part of the fabric of civil society. One of the questions I have is, should we talk about coming up with some new financial products that get women the money they need during the period of their life when they might need extra help in the house? When they, when the binds that come from caring for elderly parents or children are starting to knock them out of the workforce, and trying to figure out how to make some kind of creative structure to help shift the burdens to times of their life when they can better afford it. What do you think about that?

00:30:40

Andrew Yang: Yeah, so just to sort of show the other side of the coin, so men volunteer less if they're unemployed than employed, even though that doesn't make any sense in terms of their free time. Women show higher rates of volunteerism and going back to school when they have more time. So it's just that the numbers show clear patterns of like, different responses to non-work-related time or idleness. But I, I'm with you on the fact that right now trying to map everyone's economic prospects to the market, the market's valuation of our wages, has all sorts of distorting effects, and tend—what you're suggesting that we should just start putting money into people's hands at various points in their lives, I mean, that's really one of the underpinnings of the freedom dividend. You know, my universal basic income—

00:31:35

Eric Weinstein: I see that that's a part of it.

00:31:36

Andrew Yang: Yeah, it's like you put 1000 bucks a month into people's hands, and then that would allow us all to make different types of decisions, really from almost day one of our adulthood.

00:31:52

Eric Weinstein: Let's try a few other things that I think might be interesting. One thing that wins presidential campaigns that we don't talk much about is demographers. Demographers are sometimes asked, "Tell me some group of people that we don't know about as a voting block that nobody's figured out how to speak to." And I think I have a couple of these that are candidates, and I'd like to bounce them off—

00:32:13

Andrew Yang: Oh please, yeah, I'd like this, maybe I'll find a new audience to—

00:32:17

Eric Weinstein: Well then, okay. So the first one that I have, you know, so these are things like soccer moms was one from years past, or exurbs, between rural and suburbs, where people didn't realize that there were intermediate places. So here's one that I think is huge that hasn't been identified. Parents of super smart kids that have some kind of a learning difference that causes them to wildly underperform in school. This is something that makes me crazy because I think it's all over. Once you start seeing it, you see it everywhere. Parents are tearing their hair out—

00:32:51

Andrew Yang: Yup.

00:32:52

Eric Weinstein: Teachers can't handle the kids—

00:32:53

Andrew Yang: Nope.

00:32:54

Eric Weinstein: And there's just this maddening loss of human brilliance that is flushed down the toilet.

00:33:11

Andrew Yang: Have you come up with a name for this group?

00:33:13

Eric Weinstein: Well, I often refer to these as kids with learning superpowers, and I talk about teaching disabilities, which is the more dangerous version of this: that because people don't fit into the notion of what can be educated by one teacher teaching a room of 30 people to make the economics work, my belief is that—and I'll come up with a name for it for you—but I want to talk to all of the parents who are leading lives of despair, saying why is my kid wildly underperforming and I know how smart this kid is? Why are we doing this to ourselves and why will no one speak to it? This is, by the way, this is me and it's been in my family for four or five generations.

00:33:44

Andrew Yang: It's me too

00:33:45

Eric Weinstein: Really?

00:33:46

Andrew Yang: Well, yeah. I'm very public about the fact that my older son is autistic—

00:33:51

Eric Weinstein: I know that.

00:33:51

Andrew Yang: And that when we put him in various environments, I mean, there were very, very sharp struggles. And to me, atypical is the new normal, like neurologically atypical. And you're right that as soon as you start seeing it, you see it everywhere—and that the facts show that it's incredibly commonplace. And at this point, I think most American families have someone either in the family or someone in their social circles that resembles the description that you just put out there of this group. To me, a lot of it is that our institutions just aren't well-designed for people with different learning profiles or different approaches to the world—

00:34:37

Eric Weinstein: And yet these are very often the people who are going to found new fields, who are going to find new drugs for us, who are going to think in such different a- uncorrelated fashions, that these are very often the people that I value the most, and you never know whether the thing's going to work out because the kid every, every year is sustaining more and more trauma. Whereas these other kids, it's like, you know, I remember looking at the neurotypicals as if I was like Cinderella, watching all the other sisters go to the ball and I was sitting there scrubbing dishes. Like what? You know, every conference was Eric is underperforming. Eric can't meet his potential. Eric this or that. You know, at some point it's just like, you don't realize how much damage you're doing to maybe as much as a fifth of the country.

00:35:26

Andrew Yang: Well, someone described it as like you're getting regular, low grade psychic beating.

00:35:32

Eric Weinstein: That's pretty good.

00:35:34

Andrew Yang: And, and that's something that you obviously wouldn't wish upon anyone, much less little kids.

00:35:39

Eric Weinstein: Yeah. And by the way the autism thing, you know, I don't know whether your child is high functioning or not, but it's certainly the case that a lot of us have the idea that we almost don't want to deal with people who aren't in some sense on the spectrum or having some kind of ability to focus and to work with abstractions. Very often I think of, you know, I, I'm on top of this, I'm colorblind, and I always make the point that I see camouflage better—

00:36:08

Andrew Yang: Did you know that you're wearing bright purple right now?

00:36:12

Eric Weinstein: Stop it. That used to happen. I used to dress myself before I let my girlfriend, now wife, make these decisions. I would make terrible decisions.

00:36:21

Andrew Yang: I'm just kidding, you look great. Pia he looks great, I'm sure you had something to do with it.

00:36:25

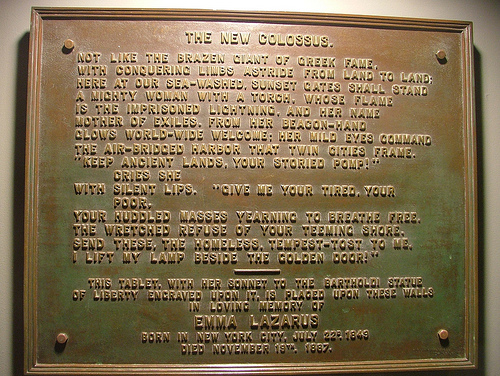

Eric Weinstein: So that would be one group. Here's another one that I think is really important. Now, I know that you are the child of immigrants and that, you know, I'm of course married to an immigrant. The temptation is for us to, sort of, be very defensive of our immigrants because we have some forces at the moment that have become very jingoistic, and I think that that's right. But I also think that we have to recognize that there is a story about immigration that's very unpleasant and ugly, which is how Americans have used immigration to redistribute wealth amongst ourselves. And effectively, the immigrant is used as a tool of redistribution, then people get angry or protective of the tool, and one of the things that I think—that's very important—is that a huge chunk of America is highly xenophilic. They like foreigners, they like traveling abroad. They like food, music—

00:37:25

Andrew Yang: You probably read Righteous Mind by Jonathan Haidt. You're probably friends with John, right?

00:37:28

Eric Weinstein: Yeah. Yeah.

00:37:30

Andrew Yang: Yeah, I figured. Okay, continue, 'cause this is what it reminds me of.

00:37:32

Eric Weinstein: Okay. The thing is that xenophilic restrictionists are a good chunk of this country. If you do a poll, and you allow for all four boxes, xenophilic, xenophobic, restrictionist, expansionist, xenophilic restrictionism is a giant cohort. Nobody speaks to it because if you say anything about restrictionism, the media will instantaneously label you a xenophobe. Can we at least distinguish the idea of the immigrants, as souls like ourselves, who have been an important part of our national tapestry, together with the fact that very often they are used as instruments of transfers of wealth? And—

00:38:17

Andrew Yang: I agree.

00:38:17

Eric Weinstein: And that we should be angry at our fellow Americans who cynically use immigration and hide behind the immigrant to take money from one sector and put it into their own pockets.

00:38:26

Andrew Yang: Or you should not be angry at someone who's angry about the immigrants.

00:38:31

Eric Weinstein: Well this is the thing—

00:38:33

Andrew Yang: Because, because there is something, like you said it's like, you know, in some ways someone can have a very legitimate grievance about the fact that there have been these instruments of wealth transfer that have been imported into our midst.

00:38:47

Eric Weinstein: So I call these the Americans who redistribute our wealth "immigrantrepreneurs", right? And the idea is that if they could use puppy dogs to redistribute our wealth, they'd use puppy dogs because nobody can be against puppies. Right? And so it's a very cynical use of the Statue of Liberty. It's something that's very difficult to talk about. But it's something that I've been talking about for a while, because I think that I'm so far in the xenophilic category it would be comical if somebody decided I actually had a problem. So I've been bold and I haven't really had the problem, but most Americans feel very uncomfortable talking about immigration because they have two different feelings. They one, have a really good feeling about the person that they know who happened to come from Uganda or India, and they have the sense that something is wrong with the story. We're going to have to disentangle it and restore something that makes us feel good about it rather than uncomfortable.

00:39:37

Andrew Yang: I agree.

00:39:39

Eric Weinstein: Great.

00:39:39

Andrew Yang: And, you know, I think I may be able to help in this regard.

00:39:44

Eric Weinstein: I think you're perfectly positioned for this.

00:39:46

Andrew Yang: You know, in part I'm the son of immigrants who loves this country, who loves that immigrants have been an incredible source of dynamism—but, you know, you can't have open borders and unrestricted immigration. I understand the sentiment where people are struggling with the fact that our country has brought many people in, either intentionally or unintentionally, in ways that are changing our economy and society in ways that in, like, some people have legitimate problems with.

00:40:26

Eric Weinstein: Yeah. I just think, I think we need to be able to have an open conversation about difficult topics around this and pull them apart. And the fact is we need, we need people to feel comfortable that it's okay to feel uncomfortable as long as you're trying to explore it—but the current president, for my money, gets way too close to jingoistic sentiment.

00:40:46

Andrew Yang: Yeah, and that's one of the natural reactions, is that if the current president says one thing, then, you know, the right thing to do is say the exact opposite. But then the nuance gets lost and then unfortunately we end up falling into these polarized camps

00:40:59

Eric Weinstein: That's why I feel like we have—it's so important not only to defeat the current president, but also to defeat the kleptocratic center of our own party as well as the regressive left that proposes as the progressive left, and then to take care of the constituents that are currently all over the spectrum in a new world. And this is one of the things I love about your slogan, which is not left or right, but forward, right?

00:41:28

Andrew Yang: Yes. That's the slogan.

00:41:29

Eric Weinstein: Yeah. And that that thing is that it's moot, it's a question of—

00:41:32

Andrew Yang: It also happens to be the truth. It's not just like—

00:41:34

Eric Weinstein: I know, that that's the thing. It's moving out of Flatland, like we've been given this smorgasbord of bad options and just say hey, I don't think I want to dine from there. I think these things are available off menu. Do you mind if I... You know, like for example, Starbucks I think will sell you a short cup of coffee, but they won't put it on the menu. You have to know that to ask for it. So I like to think of you as the guy who somehow knows that there are things that aren't on the menu.

00:41:59

Andrew Yang: I am animal style at In-N-Out. I am... Andrew Yang is animal style!

00:42:05

Eric Weinstein: Let me give you—

00:42:07

Andrew Yang: I agree that I can change the political conversation in a way that many Americans find very exciting and productive, because 25% of Americans are politically disengaged, including, I'm sure, some people watching this, and I believe it's up to 48% [that] self-identify as Independent, which is almost twice what identify as either Democratic or Republican—

00:42:27

Eric Weinstein: I'm so close to identifying as Independent. I can't stand my own party, but my feeling is I have to stay there and say hey, we're out of control in order to save the structure, because I, I—

00:42:40

Andrew Yang: Well, the two party system, I mean, I agree. That's why I'm running as a Democrat in part. It's like, well, you have these two parties. Maybe you can turn one of them into like a highly functioning party with great ideas than the rest of it, I mean, that's like an easier solution than—

00:42:54

Eric Weinstein: Look Andrew, what I really want to do is I want to reta—I want the insurgency that you and I have been sort of a part of, this loose collection of people who are thinking completely off the menu, to start retaking our institutions. We always had heterodox people of high caliber who are, you know, effectively heretics housed inside the Harvards and MITs and Caltechs, and I think we've gotten rid of that kind of—

00:43:25

Andrew Yang: Or they are there. Then they're scared shitless to, like, say the wrong thing or else they'll get—

00:43:29

Eric Weinstein: Well, do you remember the time, you remember that situation where MIT turned over Aaron Schwartz?

00:43:34

Andrew Yang: I shouldn't laugh, 'cause, I mean, it's dark.

00:43:36

Eric Weinstein: But we should laugh.

00:43:37

Andrew Yang: No, no, I mean—

00:43:38

Eric Weinstein: I'm for laughing at the dark.

00:43:40

Andrew Yang: Yeah, I laugh at the dark, it's, you know—

00:43:42

Eric Weinstein: It's like everybody knows that, but you're not allowed to do it in public. So screw that. You know, we had this situation with this guy, Aaron Schwartz—

00:43:48

Andrew Yang: Did you know Aaron?

00:43:49

Eric Weinstein: No. Did you?

00:43:51

Andrew Yang: I've, you know, he's a friend of friends.

00:43:53

Eric Weinstein: Yeah. You know, and this guy almost certainly was a pretty pure-hearted human being who was fighting the good fight. MIT is supposed to shelter those people, and instead they cooperate, you know, in turning them over.

00:44:07

Andrew Yang: As soon as you get the institutional incentives in a particular direction, then, like—I mean, this is not near, and this is just like recent, because in recent memory, but you know I stuck up for Shane Gillis, this comedian that had said—

00:44:19

Eric Weinstein: I saw that, and the the idea that, you know, you were in a position to say look, I'm the candidate—

00:44:26

Andrew Yang: He personally actually, yeah, and so if anyone should be offended, it's me. And so I think he shouldn't lose his job over it, well—

00:44:31

Eric Weinstein: Well this is the thing, the quality of mercy, or forgiveness, or just recognition that there should be space for remorse and redemption, this is what makes so much of the intolerant left feel cult-like, and I thought what you were doing was you were showing the best aspects of a truly compassionate left.

00:44:55

Andrew Yang: I was trying to be a human being, you know? Like you looked at him, being like well, like is that a job losing offence? But then the fact that NBC ended up firing him was entirely consistent with our corporate incentives, because if you look at it and say like well, is this person that we've invested a lot in that's some, a revenue generator for us? No, because he hadn't even worked for one day. It's like our corporate incentives to can him and thoughts like, you know, put an end to any controversy or advertiser or whatnot, that would be troubled by it, yeah. So it's like, so if you'd asked me, it's like hey, do you think he's going to be fired? I'd be like yeah, he's almost certainly going to be fired because that's what the corporate incentives [inaudible].

00:45:34

Eric Weinstein: Well I understand that, so one of the things that I'm really interested in doing—

00:45:37

Andrew Yang: But it, it still made me sad. Like I was like hey, this would be unusually human and forgiving if they decided to—

00:45:44

Eric Weinstein: Well, they lost a teachable moment, because one of the things that's going on is that so much of the information economy is very, very marginal in the sense that you're almost producing a public good. So for example, I slap ads on my podcasts—

00:46:00

Andrew Yang: Buy stuff from his sponsors. No I'm kidding.

00:46:02

Eric Weinstein: What I'm trying, well, what I'm trying to do is I've tried two new models, one of which I'm calling reverse sponsorship, where I shout out some great company which doesn't know that I'm going to say something positive, and maybe they become sponsors, maybe they don't, but the other one is riskvertisers, where people get to know me over long periods of time, and the hope is that you're going to say look, you're not going to catch me being horrible and bigoted and all of these things, but I might say something dangerous, like something that I just said about immigration, and will you make sure that you will not run away from me during the period where the mob descends and the frenzy is at its worst? Right? Because if we don't fix the economic models, we can't have deeper discussions because everybody's going to run away at the first sight of trouble. And so part of what we're trying to do ultimately with the advertising—

00:46:50

Andrew Yang: Look at this, pirate radio, pre-advertising.

00:47:52

Eric Weinstein: What do you think?

00:46:54

Andrew Yang: I mean, I love it. It's like, leave it to you to try and solve that kind of problem.

00:46:57

Eric Weinstein: All right, I've got some other things that I want to talk about in demographics.

00:47:01

Andrew Yang: Oh yeah, please.

00:47:02

Eric Weinstein: Okay—

00:47:02

Andrew Yang: So let me first say, I am a parent of a neurologically atypical young person. I agree with you—that I think that many of the people who have a different perspective are going to end up being contributors in highly distinctive ways. I will say that even kids who are not going to be contributors in highly distinctive ways still deserve schools that can support and accommodate them. And that, to me, these kids are like, the shorthand I use is that they're spiky. You know, it's like you have very high capacities in some respects or a different point of view, and then real challenges in other respects. And so if I send you into a social environment where there are 30 kids for one teacher, you're going to have a terrible, terrible time, you know? That's 100% predictable, and so if then you have like a critical mass of people that resemble this, then you should try and design an institution that takes that into account. And I feel so deeply for families that struggle with this, like you struggle with, it sounds like you've experienced it.

00:48:07

Eric Weinstein: Oh absolutely.

00:48:09

Andrew Yang: I have struggled with it. And you and Pia, you know, and me and Evelyn, like we have an unusual level of ability to try and, you know, manage situation, and I meet single moms around the country who have, you know, autistic or neurologically atypical kids, that don't have the means and they live in a part of the country that does not have like a lot of resources in place for kids that are different. And, it breaks my heart. Like it, the fact that there are all of these kids that are heading into these schools that are getting, you know, more than low grade psychic beatings.

00:48:44

Eric Weinstein: Oh my God. This is why I leave my DMs open on Twitter, and this is one of the number one things I do it for, is people write to me and they say I know you're really busy, but I just want to tell you, nobody had ever spoken to my situation. You're proud of something I'm always ashamed of, and—

00:48:59

Andrew Yang: I guarantee you I'm not the first presidential candidate with autism in the family.

00:49:03

Eric Weinstein: Yeah.

00:49:03

Andrew Yang: And the fact that I'm the first talking about it is, to me, long overdue and ridiculous. And—

00:49:09

Eric Weinstein: Amen.

00:49:10

Andrew Yang: And you know, and I get some of the same messages that you get, but you know, like, I want to actually try and solve the problem for those families. I mean, it makes me feel glad that they feel spoken to and that they realize they're not the only ones going through it.

00:49:22

Eric Weinstein: I want to see, I want to see more money going to figure out how do we diversify the classroom of the future—

00:49:28

Andrew Yang: Yeah.

00:49:29

Eric Weinstein: So that the load isn't born by people who don't fit the economics of the teaching model.

00:49:34

Andrew Yang: Yes. And part of it is that we regard the education of our kids as a cost, and so then the city, then, is like well, I can't afford to have like a teacher for your neurologically atypical kid. And so what we have to do is, talk about inverting the model, is you have to look at the education of our children as an investment. And then you say what's that? Like, these kids require, you know, like X and Y? Then we should make that investment with the certainty, and I share your confidence in this, that you have a couple of those kids do something highly atypical and remarkable, then that pays for whatever support, or teacher, or infrastructure—

00:50:16

Eric Weinstein: This is an underground movement. I mean, I just had a very well known professor reveal to me that he couldn't read papers—in his field. I mean, he just can't read, you know? And he has to figure out what the paper is likely to be saying. There is such a weird world of unexpected achievement.

00:50:39

Andrew Yang: And this is the demon—the demon that we have to slay, in many ways, is that the negative externalities are not being encompassed within the budgets of various institutions.

00:50:52

Eric Weinstein: Very well said.

00:50:53

Andrew Yang: But then, also, we're foregoing all of the potential positive value creation or generation from proper investment in our human capital—and another dimension too, and this is neither here nor there, but I was just with Dean Kamen in New Hampshire, and he was talking about how the FDA, like all their incentives are just to like regulate the shit out of anything. And then I said to him, I was like you know what they should start measuring is the foregone utility of keeping something away from from people, like if you had something and—

00:51:25

Eric Weinstein: What is the opportunity cost of the regulations?

00:51:27

Andrew Yang: Yeah. He had like, so he had like this prosthetic limb that he was trying to give to vets, and the FDA was making it really hard for him to do so, and he was like are you kidding me? I'm trying to give limbs to Vets who've been amputated. And so by your making it hard for me to do so, you multiply like all of the limbless Vets who aren't getting a limb, like, you know, it's like—so if you had that as like an actual measurement for the FDA, it's like you need to have these companies internalize the negative externalities of things like pollution and the rest of it, but you almost need like our institutions, like our schools and our regulatory agencies to start trying to somehow capture the potential gains from investing in our kids, or allowing a certain innovation into the market. Like, the big problems are that our measurements are really primitive. And it ends up, and you end up with binary incentives where you lose a lot of the value, and so you end up being like hey, don't have a teacher for your kid, so your kid's gonna, you know, just end up sidelined. And sidelined is like a euphemistic way for saying destroyed.

00:52:39

Eric Weinstein: I know. One of the things I wanted to do at some point—I actually ended up talking to the Heritage Foundation of all people about this—was the idea of national interest waivers so that we could have a Skunkworks with very light regulation hanging off the side of every large company. And the idea is that you would put some portion of a company, you could put some portion of the company outside, where the rules were effectively different, because you needed people to take massive risks, to be able to move super fast, to be dealing with highly non-neurotypical people.

00:53:14

Andrew Yang: And this is one of the things that drives me nuts about the political conversation is like, you get like, they get like yelled at for a particular, it's like oh, you made a mistake, duh duh duh. It's like, you kind of need to have an environment where you're going to accept a certain level of mistakes, particularly when you're talking about large scale society-wide investments, where like, of course you can't get that stuff right. And you know, it's like, and that the problem is that the political incentives are for everyone to try and avoid like a negative headline, or something that, that's—

00:53:43

Eric Weinstein: Look, a lot of us are very disagreeable, very difficult to deal with. And, you know, I saw you pick up endorsements from people like Elon Musk, you know, which is... Then I hear his personal life being criticized, I was like I don't really care. This guy is responsible for how much—

00:54:02

Andrew Yang: Advancing the species.

00:54:03

Eric Weinstein: How much adva—right, how much innovation? If he's got a few foibles, let's give him some privacy. Let him be in peace and just recognize that we're getting an unbelievable deal, and yet this desire to somehow stamp out outliers—I mean, outliers are essential to the American project.

00:54:22

Andrew Yang: Yes, I could not agree more. And you know I, I'd consider myself—it's pretty funny Eric, 'cause I, you know, I think I had, in many ways, like a highly conventional upbringing that helped—like, I feel like I'm sort of a hybrid where, to the extent that I was highly contrarian or dissimilar, you know it's like, I, you know, I've, I came up through a series of institutions in an era where, you know, I think I learned to adapt. But then I look at my boys and I think to myself that, you know, that their way of life is going to be very, very different than mine. I'm sure yours too, 'cause we came of age in a different era.

00:55:10

Eric Weinstein: Well this is true. I mean I was just talking about this actually, with Bret Easton Ellis sitting in that chair that, you know, I grew up as part of this free range world largely before Etan Patz got kidnapped and the milk carton kids changed everything. I worry about the sort of—we were too free range and these kids are too sheltered, that we have to find some new mix. But I want to get to another issue.

00:55:33

Andrew Yang: Give me one more demographic.

00:55:34

Eric Weinstein: Okay.

00:55:35

Andrew Yang: Yes.

00:55:36

Eric Weinstein: Let's do it. And then we'll, we'll close it out. I want to talk about something which really makes me angry and excited. I think that America has, without question, some of the finest sources, educationally, for brilliance in STEM subjects. And we've pretended for a very long time that Americans are not good at STEM, that we are disinterested in STEM, that STEM careers are fantastic when many of them are pretty shitty, and that we don't recognize that the entire STEM complex is suffused with bullshit. Because the model, the economic model for investing in basic research went belly up because the universities were built on a growth model that was unsustainable. And I want to stop lying.

00:56:26

So one, I want to start recognizing that we have high schools that have more Nobel prizes than all of China, that we are using Chinese labor and other Asian countries, not just because we are exporting education as a good, but because we have a cryptic labor market in basic research where we pretend people are students when they're actually workers. We pretend that we're importing them to educate them, but actually what we're trying to do is use a poverty differential. We have our own people who are really fantastic because they're not very obedient, and instead people prefer obedient people coming in who are here on temporary visas, therefore they have to follow orders.

00:57:11

The entire National Science Foundation, National Academy of Science complex is bizarrely suffused with nonsense. And because of this, we can't actually have the national academies adjudicate what's true because they are the prime offender of this. How do we get back to a situation which we can recognize that we have a Stuyvesant or a Bronx Science, you know, or a Far Rockaway, or any of these unbelievable high schools that are turning out people who desperately want to do STEM subjects. They're not being paid when they finally get their degrees at an appropriate level.

00:57:46

Andrew Yang: Yeah.

00:57:47

Eric Weinstein: They've been secretly studied by our science complex, because these career paths are known to be crappy, and we have completely suffused this with a mis-description so that nobody can actually fix any problems.

00:58:01

Andrew Yang: That's an incredible description. And to me, the lack of proper resources for basic research, for things that ended up being foundational for many of our current industries—

00:58:15

Eric Weinstein: It's the biggest bargain in the world. It's just the future you're investing in.

00:58:18

Andrew Yang: It's just right now we're so brainwashed by market-driven thinking, that if there's not some short-term profitability tied to it or there's no drug company funding it, or something along those lines that—and this is something that the government, historically has been the leader in where it said, you know what, we can lay the foundation and create paths for people to be able to do basic research, the benefits of which will be unclear. They may not exist. They may not materialize for decades, but it's similar to what we're talking about with the neurologically atypical kids, is that like a few of them pay off and then the payoff can be unfathomably significant.

00:59:00

Eric Weinstein: Well we call this long vol. investing in hedge fund land, where most things don't work out, but a few that do pay for all of the losers.

00:59:09

Andrew Yang: Yup. Yeah. And right now the, yeah. To me, this is a role where historically, the government has led, and you need a government willing to make long-term sustained investments that may only pay off way down the road and may not pay off, but you still need to be able to make them.

00:59:29

Eric Weinstein: Well, I also, you know, the other weird part of this is that by using our own people, and letting in particular China know that it can't operate a relatively totalitarian government over there and have the benefit of freedom over here with a pipeline for all of our innovations to immediately go back over there—China needs to be induced in some sense to understand that they can't get by without giving their people freedom.

00:59:58

And what they're right now doing is that they're using our freedom and a periscope by which they can see everything that we're doing. And if we actually cut that off, I know that the universities are going to scream bloody murder, but what's going to happen is China's going to have to start investing in its—the right of its own people to give the middle finger, because irreverence is the secret of American ingenuity.

01:00:21

Andrew Yang: Yeah. Yeah. You know, this reminds me of a joke that they told in artificial intelligence, which is, "How far behind is China than the US in AI?" And the answer is 12 hours. And you say, you know, obviously they wake up and then they see what we did.

01:00:37

Eric Weinstein: Andrew, I can't tell you how fantastic it is, to have you come into the studio. You're coming off of this big rally in MacArthur park.* You're welcome anytime to come back. I'd love to continue the conversation when you're next in LA—

* Note: The following sentence was cut from the YouTube version of the podcast: "I know that it's late for both of us."

01:00:47

Andrew Yang: I would love this too, man, this feels to me like half a conversation. We're going to have to have the second half at some other time. So if you enjoyed this convo, let Eric know, and then hopefully he'll have me back. And if you'd like to join the Yang Gang, you should know we are very, very cheap gang to join.

01:01:04

Eric Weinstein: Is that right?

01:01:05

Andrew Yang: Well, our average donation is only $25. So, our fans are even cheaper than Bernie's, which no one even knew could be a thing in politics, but here it is. But you get $25 times enough people and you wind up putting up very very big numbers—and you'll see like, we're already into the eight digits as a campaign, and we can take this whole thing, we can contend, because a lot of people watching this right now, you're ignoring politics as usual. We can actually have a different sort of politics that takes real thinking, real ideas, real solutions, and brings them to the highest levels of our government. It just needs enough Erics and Pias and you all watching it at home to say I prefer this to the stuff I'm getting through the cable TV networks—

01:01:50

Eric Weinstein: Well, Andrew, you know one of the things I think that's been great about watching your meteoric rise is that you are outside of control without being out of control—

01:01:58

Andrew Yang: Thank you.

01:01:59

Eric Weinstein: And that having a kind of a mature person, who's not easily bought or swayed, who's speaking in a way that nobody knows what he's going to say next, has been hugely positive for the entire process, so thank you very much.

01:02:09

Andrew Yang: Well, thank you. You know, the only currency I answer to is ideas and humanity. Like you, you know, you put a good idea in front of me or a good person, I listen.

01:02:23

Eric Weinstein: Well, you've been that way since before all the success. So we wish you continued success, and we'll have you back here the next time you're in LA with a little bit of time.

01:02:31

Andrew Yang: Would love that, brother. Thank you.

01:02:32

Eric Weinstein: All right. Thanks, you've been through The Portal with Andrew Yang, presidential candidate for 2020, and telling us to Make America Think Harder.

01:02:42

Andrew Yang: Yes. This man is going to make you think harder all the time.

01:02:45

Eric Weinstein: All right. Be well everybody

Markup for Portal Player[edit]

Eric Weinstein interviews Andrew Yang, Episode 8 of The Portal

Yang a political rally held in Los Angeles at MacArthur Park on 30 September 2019 (article).

Yang Gang

"Yang Gang" is a term used to describe the collective of Andrew Yang supporters.

For a more detailed explanation of Eric's criticisms of said 'superstructure' see Slipping the DISC.

Embedded growth obligation or EGO.

Freedom Dividend

Andrew would implement the Freedom Dividend, a universal basic income of $1,000/month, $12,000 a year, for every American adult over the age of 18. This is independent of one’s work status or any other factor. This would enable all Americans to pay their bills, educate themselves, start businesses, be more creative, stay healthy, relocate for work, spend time with their children, take care of loved ones, and have a real stake in the future.

Other than regular increases to keep up the cost of living, any change to the Freedom Dividend would require a constitutional amendment.

It will be illegal to lend or borrow against one’s Dividend.

Yang's Background

Andrew M. Yang is an American political commentator, lawyer, entrepreneur, and philanthropist. Originally a corporate lawyer, Yang began working in various startups and early stage growth companies as a founder or executive from 2000 to 2009. In 2011, he founded Venture for America (VFA), a nonprofit organization focused on creating jobs in cities struggling to recover from the Great Recession. He then ran as a candidate in the 2020 Democratic presidential primaries. wiki

Healthcare.gov Rollout Failure

Healthcare.gov was officially launched on 1 October 2013 covering residents of 36 states that did not create and manage their own healthcare exchange. Problems with the website were apparent immediately. High website demand (250,000 users [5 times more than expected]) caused the website to go down within 2 hours of launch. While website capacity was initially cited as the main issue, additional problems arose mainly due to the website design not being complete. Users cited issues such as drop down menus not being complete and insurance companies cited issues with user data not being correct or complete when it reached them.

In addition, the websites login feature (which is the first step to accessing the website) could handle even less traffic than the main website which created a huge bottleneck. Due to poor planning, this same log in method was also used by website technicians, making it extremely difficult for them to log in and troubleshoot problems.

A total of 6 users completed and submitted their applications and selected a health insurance plan on the first day.

Through a large amount of troubleshooting, bringing in new contractors, and increased management, the website could handle 35,000 concurrent users at a time by December 1 and a total of 1.2 million customers signed up for a healthcare plan by 28 December, when the open enrollment period officially ended.(source)

Marketplace Lite

The 'maverick Silicon Valley types' referred to is the start up Marketplace Lite. For a more in-depth story on their work on Healthcare.gov see the following link (source).

Brad DeLong

James Bradford "Brad" DeLong is an economic historian who is professor of Economics at the University of California, Berkeley. DeLong served as Deputy Assistant Secretary of the U.S. Department of the Treasury in the Clinton Administration under Lawrence Summers.(blog)(wiki)

NAFTA

The North American Free Trade Agreement was an agreement signed by Canada, Mexico, and the United States, creating a trilateral trade bloc in North America. The agreement came into force on January 1, 1994, and superseded the 1988 Canada–United States Free Trade Agreement between the United States and Canada.(wiki)

Social Darwinism

Social Darwinism is any of various theories of society which emerged in the United Kingdom, North America, and Western Europe in the 1870s, claiming to apply biological concepts of natural selection and survival of the fittest to sociology and politics.(wiki)

Jingoistic - characterized by extreme patriotism, especially in the form of aggressive or warlike foreign policy

Alan Greenspan (born March 6, 1926) is an American economist who served as Chair of the Federal Reserve of the United States from 1987 to 2006. He currently works as a private adviser and provides consulting for firms through his company, Greenspan Associates LLC. First appointed Federal Reserve chairman by President Ronald Reagan in August 1987, he was reappointed at successive four-year intervals until retiring on January 31, 2006, after the second-longest tenure in the position (behind William McChesney Martin).

Larry Summers (born November 30, 1954) is an American economist, former Vice President of Development Economics and Chief Economist of the World Bank (1991–93), senior U.S. Treasury Department official throughout President Clinton's administration (ultimately Treasury Secretary, 1999–2001), and former director of the National Economic Council for President Obama (2009–2010). He is a former president of Harvard University (2001–2006), where he is currently (as of March, 2017) a professor and director of the Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business and Government at Harvard's Kennedy School of Government.

Paul Krugman (born February 28, 1953) is an American economist who is the Distinguished Professor of Economics at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, and a columnist for The New York Times. In 2008, Krugman was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his contributions to New Trade Theory and New Economic Geography. The Prize Committee cited Krugman's work explaining the patterns of international trade and the geographic distribution of economic activity, by examining the effects of economies of scale and of consumer preferences for diverse goods and services.

ad infinitum - again and again in the same way; forever.

Magician's Choice

The magician's choice is also known as equivocation.

Samizdat (Russian: Самизда́т, lit. "self-publishing")

Samizdat was a form of dissident activity across the Eastern Bloc in which individuals reproduced censored and underground makeshift publications, often by hand, and passed the documents from reader to reader.(wiki)

William Tell

This story invokes the trope of shooting an apple upon a child's head with a bow or crossbow. The motif displays the skill of the marksman in a situation where failure is of great consequence.(wiki)

Pia Malaney Co-Founder and Director of The Center for Innovation, Growth and Society and Senior Economist at the Institute for New Economic Thinking. (bio). She is also Eric's wife.

Pia Malaney Co-Founder and Director of The Center for Innovation, Growth and Society and Senior Economist at the Institute for New Economic Thinking. (bio). She is also Eric's wife.

Is-a vs Has-a

In object oriented languages, such as Java, and Is-a relationship is known as inheritance and a Has-a relationship is known as composition.

Am example of an Is-a relationship is as follows, a Potato is a vegetable, a Bus is a vehicle, a Bulb is an electronic device and so on. One of the properties of inheritance is that inheritance is unidirectional in nature. Like we can say that a house is a building. But not all buildings are houses.